Where Oceans Join: Landscapes, Seascapes, Archipelagoes in Circum-Caribbean Ecologies

About the Event

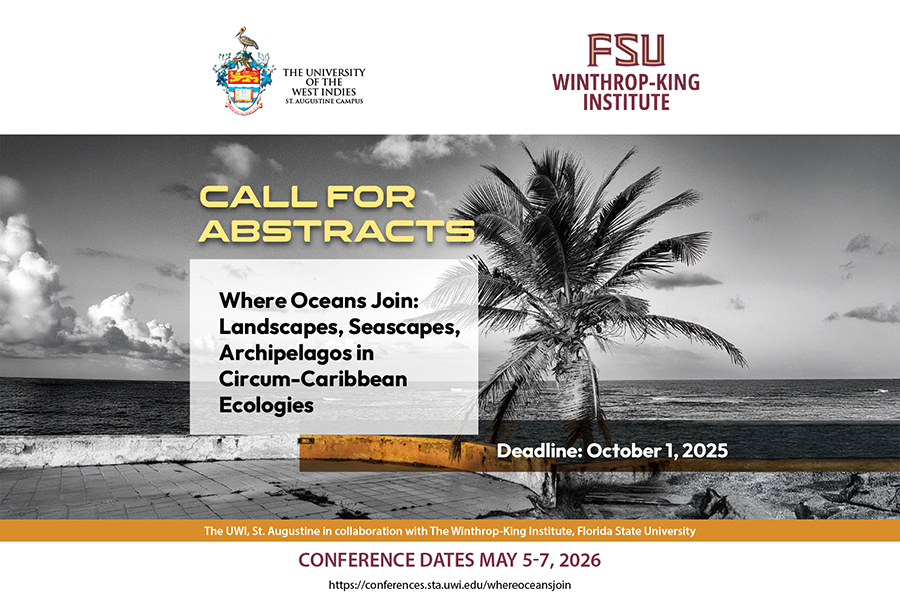

The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, in collaboration with The Winthrop-King Institute, Florida State University presents:

"Where Oceans Join: Landscapes, Seascapes, Archipelagoes in Circum-Caribbean Ecologies"

International Conference

Confirmed Keynote Speakers

Malcolm Ferdinand (CNRS, IRISSO Université Paris Dauphine)

Deborah Jack (Professor of Art, New Jersey City University)

Organizers

Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw (UWI) and Martin Munro (FSU)

Call For Papers

There are the highest plateaus of Haiti, where a horse dies, lightning-struck by the age-old killer storm at Hinche. Next to it, his master contemplates the land he believed sound and expansive.mHe does not yet know that he is participating in the island’s absence of equilibrium. But this sudden access to terrestrial madness illuminates his heart: he begins to think about the other Caribbean islands, their volcanoes their earthquakes, their hurricanes.

(Suzanne Césaire, “The Great Camouflage”)

We islanders aren’t familiar with [the] vertigo of the earth. We bind vertigo to its greatest tension, we must contract our space in order to live there. Our field is of the sea that limits and opens. The island presumes other islands. Antilles. (Édouard Glissant, Poetic Intention)

Le pays dépend souvent du coeur de l’homme: il est miniscule si le coeur est petit, et immense si le coeur est grand. (Simone Schwarz- Bart, Pluie et vent sure Télumée Miracle)

The fluid, marine-like quality in much Caribbean writing, art, and thought—the sea as history, the unity as submarine—has to do with the complicated relationship with the land, especially for those whose ancestors were transported there to be either enslaved or indentured. One cannot understand the importance of the sea to Caribbean authors and artists without registering that of the land. As Helen Tiffin writes, the legacies of history are still relevant for people’s notions of land and belonging: “Unlike indigenous peoples, such relative ‘newcomers’ bring with them the values, cultural memories, knowledge, and traditions of their former environments, a prior ‘natural’ history of being-in-the-world that, consciously or unconsciously, implicitly or explicitly, influences (through expectation, comparison, and contrast) their perceptions of the new” (2005, 199). It follows that the representation of the land and the landscape is not straightforward, “imbricated as it is in crucial ways with histories of transplantation, slavery, and colonialism and with imported European traditions of land and landscape perception and representation” (200).

Theorists of the Anthropocene have begun to address the contemporary ramifications of such a colonial relationship to the Caribbean land. Elizabeth DeLoughrey, for instance, writes of the Caribbean islands as “originary spaces of the Anthropocene,” given the long history there of “transatlantic empire and slavery, the radical dislocation of humans from their ancestral soil, and a violent irruption of modernity that predates the industrialization of nineteenth-century Europe” (2019, 35). Arguing that since capitalism was “constituted by transatlantic slavery and the plantation system,” DeLoughrey points out that the term “Plantationocene” has recently been used “to further specify the ways in which an economic and political system of empire is exacted on the earth” (35). DeLoughrey’s concerns are echoed in the work of Malcolm Ferdinand, who writes of the “modern tempest” and the need to address the “double fracture [that] separates the colonial history of the world from its environmental history” (2022, 3). In Ferdinand’s terms, as the “eye of modernity's hurricane, the Caribbean is that center where the sunny lull was wrongly confused for paradise, the fixed point of a global acceleration sucking up African villages, Amerindian societies, and European sails” (2022, 12). For Valérie Loichot, the sea is a site of “unritual,” which in the context of Caribbean history is “a state more absolute than desecration or defilement” in the memorialization of the unremembered dead of the Middle Passage. Unritual, she writes, “is the obstruction of the sacred in the first place” (2020, 7). Drawing on Glissant, she argues that “ecological solidarity, the relational sacred, and artistic compositeness appear as the modes of healing and dealing with the unritual” (2020, 24). One vital way of understanding these processes and crises and the ongoing effects they have had on the imagination of Caribbean people, especially in regard to the land, the sea, and the environment, DeLoughrey insists (and Ferdinand and Loichot implicitly agree), is through a “critical engagement with narrative,” and specifically, as she emphasizes in her recent work, the uses of allegory, which was “integral to representing the colonial violence of transatlantic empire and the plantation” (35).

Taking up DeLoughrey’s insistence on the importance of narrative, art, and new ways of thinking the Caribbean environment, this conference invites paper and panel proposals in English, French, or Spanish, on themes related to the ecologies of the circum-Caribbean region, an expansive space that includes the Lesser and Greater Antilles, the Caribbean coasts of South and Central America, the Guianas, and Florida and the U.S. Gulf South. The conference to be held at The University of the West Indies campus at St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago in May 2026 will bring together scholars, practitioners, activists, scientists, artists, writers, and members of the public. Our aim is to imagine and conceive of Caribbean ideas, approaches, and solutions to the environmental issues that each space faces. We do so in a collective, Caribbean spirit, meeting in new regions of thought and creativity, as Glissant puts it, “where the oceans join.”

Possible Themes Include

- Lands

- Water

- Travel

- Tourism

- Translocality

- The senses

- Soundscapes

- Caribbean environmentalisms

- Caribbean indigenisms

- Ecocriticisms

- Dislocation

- Disasters

- Exiles

- Memory

- Futures

- Languages

- Visual art

- Literature

- Music

- Gender