From the Sahara to the Sahel: Nomadic Voices, Cultures, and Literatures

WINTHROP-KING INSTITUTE INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM

February 8 - 9, 2024

Speakers

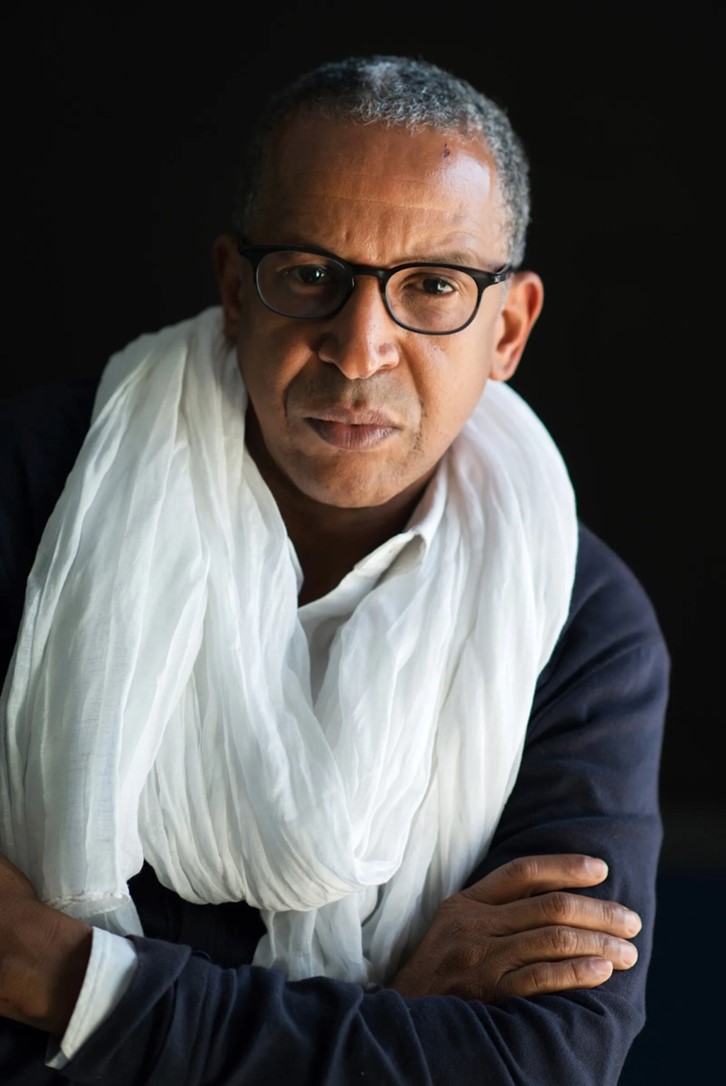

Film director and producer Abderrahmane Sissako was born on October 13, 1961, and has extensive experience working in Mali and France. Sissako is among the select group of Sub-Saharan African filmmakers who are regarded as world-class, alongside Ousmane Sembène, Souleymane Cissé, Idrissa Ouedraogo, and Djibril Diop Mambety. His film Waiting for Happiness (Heremakono), which won the FIPRESCI Prize, was shown as part of the official Un Certain Regard selection at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival. His 2007 film Bamako was well-received. Globalization, exile, and population displacement are some of Sissako's themes. Timbuktu, his 2014 film, was chosen to compete in the main competition section of the 2014 Cannes Film Festival for the Palme d'Or.

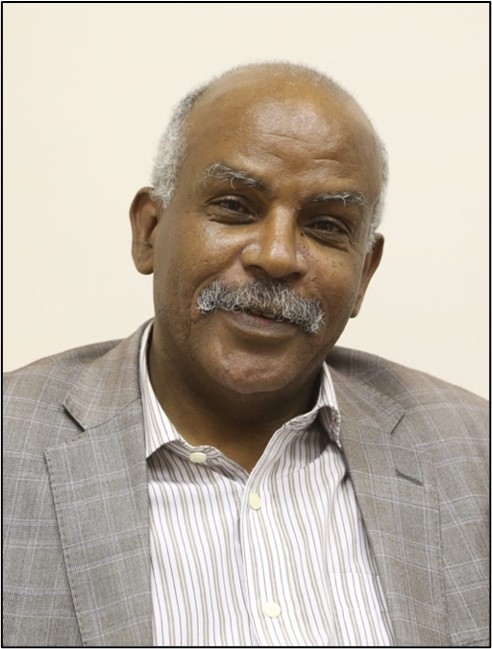

Mbarek Ould Beyrouk est né à Atar, une ville du nord de la Mauritanie, en 1957. Il a poursuivi une carrière de journaliste après avoir étudié le droit à Casablanca et à Rabat, au Maroc. Beyrouk a créé "Mauritanie-Demain", premier journal indépendant du pays et référence pour les intellectuels mauriciens aspirant à la démocratie et à la liberté d'expression, en 1988. Le journal a été confronté à de nombreuses difficultés, dont la censure permanente jusqu'à sa fermeture en 1994. Beyrouk a rejoint l'organisme de régulation de la presse, la Haute Autorité de la Presse et de l'Audiovisuel, en 2006. Après avoir rejoint la Présidence de la République en 2015, Beyrouk en a été le conseiller culturel jusqu'à son départ en 2021. Beyrouk est l'auteur d'un recueil de nouvelles ainsi que de sept romans. Son premier livre, « Et le ciel a oublié de pleuvoir », publié en 2006, a reçu le Prix du roman maghrébin de l'association France-Maghreb. Son troisième livre, « Le Tambour des larmes », a été publié en 2015 aux éditions franco-tunisiennes Elyzad. Il a reçu le Prix du roman métis de la Réunion ainsi que le Prix Ahmadou Kourouma du Salon du livre de Genève. En 2023, son album « Saara » de 2022 reçoit le prix Cheikh Hamidou Kane de littérature internationale.

Mbarek Ould Beyrouk was born in the northern Mauritanian town of Atar in 1957. He pursued a career in journalism after studying law in Casablanca and Rabat, Morocco. Beyrouk established "Mauritania-Demain," the nation's first independent newspaper and a point of reference for intellectuals in Mauritius who aspire to democracy and freedom of expression, in 1988. The newspaper faced several difficulties, one of which was ongoing censorship until its closure in 1994. Beyrouk joined the press regulatory body, the High Authority of the Press and Audiovisual, in 2006. After joining the Republic's Presidency in 2015, Beyrouk served as its Cultural Advisor until leaving in 2021.

Beyrouk is the author of a collection of short stories as well as seven novels. His debut book, "Et le ciel a oublié de pleuvoir," which was released in 2006, was awarded the France-Maghreb association's Maghrebin Novel Prize. His third book, "Le tambour des larmes," was published in 2015 by the Franco-Tunisian publishing house Elyzad. It was awarded the Métis Novel Prize by Réunion as well as the Ahmadou Kourouma Prize from the Geneva Book Fair. In 2023, his 2022 release "Saara" was awarded the Cheikh Hamidou Kane Prize for International Literature.

Abstract: Sahara, désert où s’embrassent des cultures

Le désert n’est pas désert. Chaque dune, chaque arpent de sable a un nom, une histoire, une tribu qui y est attachée. Le Sahara fut toujours terre d’affrontements des empires mais aussi de rencontres et de confluences des cultures. Toutes les grandes religions du monde, islam, judaïsme, christianisme ont leurs marques là, tous les grands ensembles du continent aussi.

Le Sahara est surtout le lieu où les deux Afriques, celle qu’on dit du Nord et celle du Sud se sont fortement embrassées. Et de là ont émané des littératures métissées qui s’habillent parfois du manteau des langues étrangères héritées de la période coloniale, mais qui restent enracinées dans leur milieu culturel

Bien qu’écrivant en Français, nous restons nous –même, des témoins de l’histoire et des cultures de nos peoples.

“Sahara, a hub of cultural connections”

The desert is not deserted. Each dune, each acre of sand has a name, a history, a tribe attached to it. The Sahara has always been a land of imperial battles, as well as cultural encounters and confluence. Many religions (Islam, Judaism, and Christianity), as well as many of the continent’s great nations are tied to this region.

The Sahara is, above all, a place where the two Africas, North and South, connect in a powerful embrace. From this alliance, mixed and complex literatures have emerged, sometimes coated in foreign tongues inherited from colonial times, yet always rooted in their cultural source.

Although we may write in French, we remain ourselves, witnesses to our people’s history and cultures.

Dr. Alioune Sow is Associate Professor of French and African Studies jointly appointed in the Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures and the Center for African Studies at the University of Florida. His research interests include democratic transition and cultural forms in francophone West Africa, focusing especially on memoirs, theater, and films in Mali, as well as the history of ideas in the Sahel, migration, and theater practices in France. He is currently completing a book project entitled Transitional memoirs: narration and memory in contemporary Mali, which examines the interplay between letters, politics, and the cultures of memory in post military Mali and in the Sahel. His articles and chapters on memoirs and confessions in democratic Mali, refugee theater in Bamako, Malian cinema and military, Malian television serials and democratic experience, have been published in the Journal of Modern African Studies, Critical Interventions, African Studies Review, Social Dynamics, Biography among others. He has also edited special issues of Cahiers d'Études Africaines and Etudes Littéraires Africaines and contributed as an editor and author to the Oxford handbook of the African Sahel.Vestiges et Vertiges appeared with Artois Presses Université in 2011.

Abstract: Memories of the Sahara

This lecture will trace the meanings of the Sahara Desert in the Sahelian imagination. Using mainly memoirs and autobiographies, the lecture will examine the prevailing and often competing perceptions and representations of the Sahara, ranging from the desert as a privileged site of knowledge production and cultural exchanges, a sovereign territory and political entity, a place of meditation and regeneration, to a hostile and dreaded environment of repression. The lecture will investigate how these accounts and representations engage with Sahelian political developments and experiences (colonization, decolonization, militarism, democratization, migration) and can be valuable in assembling a “biography” of the Sahara, to use Braudel (1949) and Davis (2017) concepts.

Dr. Joseph Hellweg is a cultural anthropologist and associate professor of religion at Florida State University. He has done ethnographic research in French and Manding among dozo hunters and queer NGOs in Côte d’Ivoire and N’ko teachers and healers in Guinea and Mali and taught research methods on a Fulbright Fellowship at the University of Kankan. He has published two books—Hunting the Ethical State: The Benkadi Movement of Côte d’Ivoire, U. Chicago 2011) and Anthropologie, les premiers pas (L’Harmattan, 2011), and he has published book chapters and articles in various venues. He is also deputy editor of the Journal of Religion in Africa (Brill) and co-edits the book series, “Religion in Transforming Africa” (James Currey/Boydell & Brewer, UK), and the journal, Mande Studies (Indiana University Press).

Abstract: « Les droits humains dans un empire du Sahel: oralité, alphabétisation et la Charte de Kouroukan Fouga »

Auteur guinéen et inventeur de l’alphabet N’ko, Solomana Kanté (1922-1987), a affirmé, dans son ouvrage en langue mandingue, Histoire du Mandé (2008), que Soundjata Keita, le légendaire fondateur de l’empire médiéval malien, a inventé les droits humains lors d’une assemblée au treizième siècle dans un champ appelé le Kouroukan Fouga. En revanche, l’anthropologue français Jean-Loup Amselle rejette le récit de Kanté comme une fiction. Il accuse Kanté d’avoir plagié à la fois le « droit coutumier » autochtone ouest-africain et l’érudition de l’administrateur colonial Maurice Delafosse (Amselle 2011, 449) pour inventer une histoire fabriquée que Kanté prétend plutôt avoir dérivée de sources orales ouest-africaines.

Et si Kanté croyait avoir trouvé des analogies avec les principes des droits humains dans les pratiques qui structuraient l’Afrique de l’Ouest précoloniale ? Et s’il avait trouvé, dans de telles pratiques, des notions analogues aux déclarations écrites des pays du Nord sur les droits humains ? Et si, en d’autres termes, il critiquait notre compréhension du support écrit du discours mondial sur les droits humains ainsi que la primauté de ce discours ?

Je suggère que Kanté avait l’intention de décoloniser le discours sur les droits humains en « déconstruisant son sujet », pour reprendre la phrase de Derrida (1992) tirée de sa conférence d’Amnesty International à Oxford. Kanté a fait une place aux orateurs mandingues dans le discours sur les droits humains en valorisant leurs délibérations morales. Tout comme chaque nouvelle déclaration des droits humains a étendu les droits à de nouvelles catégories de personnes, selon Derrida, Solomana Kanté a construit sur les pratiques culturelles ouest-africaines une nouvelle conceptualisation des droits au-delà du monopole des pays du Nord.

“Human Rights in an Empire of the Sahel: Orality, Literacy, and the Charter of Kurukan Fuga” Joseph Hellweg, Florida State University Guinean author and inventor of the N’ko alphabet, Solomana Kanté (1922-1987), claimed, in his Manding-language History of Mande (2008), that Sunjata Keita, the legendary founder of the medieval Malian empire, invented human rights at a thirteenth-century assembly at a field called Kurukan Fuga. In contrast, French anthropologist, Jean-Loup Amselle, dismisses Kanté’s narrative as fiction. He accuses Kanté of having plagiarized both West African “customary law” and the scholarship of colonial administrator Maurice Delafosse (Amselle 2011, 449) to invent a fabricated history that Kanté claims instead to have derived from West African oral sources.

But what if Kanté believed he had found analogs of human rights protections in the conventions that structured precolonial West Africa? What if he had located, in such practices, notions analogous to the Global North’s written human rights declarations? What if, in other words, he was critiquing our understanding of the written medium of global human rights as well as the primacy of this discourse? I suggest that Kanté intended to decolonize human rights rhetoric by “deconstructing its subject,” to borrow Derrida’s (1992) phrase from his Oxford Amnesty Lecture. Kanté made a place for Manding speakers within human rights discourse by valorizing their moral deliberations. Just as each new human rights declaration, according to Derrida, has extended rights to new categories of persons, so too did Solomana Kanté, building on West African cultural practices a new conceptualization of human rights beyond their monopoly by the Global North.

Dr. Brigitte Tsobgny holds a PhD in French and Francophone Studies at Florida State University in 2023. She is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at Emory University. She is interested in 19th, 20th, and 21st century environmental issues in French and Francophone literature and film. Her current research centers on water issues – its unequal distribution, its shortage in certain parts of the globe, access to drinking water, droughts, floods, increasingly violent hurricanes, melting of glaciers, consequences of rising sea levels due to global warming, pollution, and displacement of populations. In her previous research works, she paid particular attention to literature and films focused on the environmental problems caused by the triple disaster that occurred in Japan in 2011 and its ramifications with environmental injustices as well as economic, health, social, political, cultural, philosophical, and civilizational questions. In some of her research works, her interest in science and the environment is combined with a postcolonial approach. Through this lens, she has studied the works of Véronique Tadjo, JeanClaude Charles, Jacques-Stephen Alexis, Boualem Sansal, and Yasmina Khadra. She is also the author of several novels, some of which are science-related.

Abstract: Le Sahara de Yasmina Khadra, une terre généreuse. Le désert est souvent synonyme de terre aride, austère, voire hostile. Dans Ce que le mirage doit à l’oasis, Yasmina Khadra nous fait découvrir son Sahara natal autrement. Les contrées silencieuses et dénudées de ce désert deviennent généreuses. Tout dépend de la manière dont on voit la générosité. Dans cette présentation, je me propose de montrer comment Khadra nous révèle les trésors cachés du Sahara. Cette terre a beaucoup à offrir, suggère l’auteur de Ce que le mirage doit à l’oasis. Pour jouir de ses richesses, il faut savoir la regarder, il faut savoir l’écouter, il faut savoir se délecter de ses spectacles. Dans ses oasis, un homme en haillons peut s’avérer être un prince digne, à condition qu’on mesure la noblesse à l’aune des valeurs humaines. Au-delà de la générosité de ses enfants, le Sahara est une terre propice à la réflexion, à l’inspiration, à la rédemption. Il peut humaniser et apaiser les esprits les plus tourmentés. Pour Yasmina Khadra, « le mortel qui n’est pas venu se désaltérer dans [s]es sources n’aura vécu sa vie qu’à moitié » (111), car le Sahara est surtout une terre de sagesse « pour celui qui veut renaitre à la beauté des choses, à l’amour et à la fraternité » (121).

“Yasmina Khadra’s Sahara, a generous land.”

The desert is usually synonymous with barren, even hostile, land. In Ce que le mirage doit à l’oasis (What the mirage ows the oasis), Yasmina Khadra lets us into his native Sahara through a different point of view. The silent, stripped lands become generous. It all depends on our definition of generosity. In this presentation, I will show how Khadra reveals the Sahara’s hidden treasures to us. This region has a lot to offer, as Khadra suggests. To enjoy its riches, one needs to know how to look at it, listen to it, and delight in its spectacles. In its oases, a man clothed in rags can prove to be a noble prince, if we measure nobility in terms of human values. Beyond the generosity of its children, the Sahara is ideal for thought, inspiration, and redemption. It can humanize and appease the most tormented spirits. According to Yasmina Khadra, “the mortal that hasn’t quenched their thirst in [its] springs will have lived half a life.” (111), because the Sahara is, above all, a land of wisdom “for those who want to be reborn in beauty, love, and fraternity.” (121)

Dr. Tara F. Deubel is Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of South Florida in Tampa. She received her doctorate in anthropology from the University of Arizona (2010). Her research interests include gender and family law, migration, language and performance, visual anthropology, and African and Middle Eastern Studies. She has worked in the Sahara and Sahel regions of West and North Africa for over twenty years in urban and rural communities doing ethnographic and applied projects. She is the co-editor of Saharan Crossroads: Exploring Historical, Cultural and Artistic Linkages between North and West Africa (2014). She is currently doing research on sub-Saharan African migrant populations in Morocco and indigenous Amazigh women’s argan oil production in the region of Agadir.

Abstrat: Forced Immobility and Sub-Saharan African Migrant Experiences in Southern Morocco

While scholarly attention has focused on sub-Saharan African migration to Europe, there are few studies of the increasing number of migrants settling in Morocco for extended periods of time. These migrants endure the physical and psychological burdens of a liminal existence and discrimination as they integrate in Moroccan society. This presentation is based on findings from a three-year ethnographic study of over 100 migrants originating from West and Central Africa who reside in Agadir and surrounding areas in the Souss region. Migrants' decisions on their trajectories hinge on evaluating the risks and benefits of continuing north to Europe, staying in Morocco, or returning south to their countries of origin. In their efforts to find work, acquire legal status, develop relationships, and access state services, sub-Saharans attempt to maintain their dignity and sense of self amid the challenges and precarity of the migrant experience.

Dr. Heide Castañeda is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of South Florida. Her research areas include critical border studies, political and legal anthropology, medical anthropology, migration, migrant health, citizenship, focusing on the U.S./Mexico border, Mexico, Germany, and Morocco. She is the author of Borders of Belonging: Struggle and Solidarity in Mixed-Status Immigrant Families (Stanford University Press, 2019) and co-editor of Unequal Coverage: The Experience of Health Care Reform in the United States (NYU Press, 2018). Her latest book is Migration and Health: Critical Perspectives (Routledge, 2023).

Dr. Castañeda has also published dozens of research articles on migration and health care access for immigrant populations. Her work has been funded by the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, the Fulbright Program, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), and the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research.

Abstract: The Diasporic Tamazgha: Exploring Amazigh Lives in the U.S. using Indigeneity-Informed Approaches to Borders and Migration

How can an Indigeneity-informed approach reorient scholarship on borders and migration? Drawing from ethnographic data with Imazighen living in the U.S., I assess the implications of Tamazgha, a geographic neologism that serves as replacement for Maghreb or North Africa, arguing for its potential to push the boundaries of current paradigms by 1) decentering and reorienting geocultural spaces; 2) offering a long-overdue Indigenous perspective on mobility and migration; and 3) providing insights about the relational nature of diasporic Indigeneity. The discussion builds upon voices of everyday Imazighen as they reflect on their relationship with the construct of Tamazgha through interactions, encounters, and experiences in their daily lives. From these voices, we learn how people construct alternative geographies of belonging and formative meaning in the diaspora, produced in relation to particular people and spaces.